Pilot Officer Horace Horne - 615 Squadron and The Battle of France

Horace Eldred Horne Jr. was born in Leicester, England, October 9th, 1915, the son of Horace Horne Sr. and Florence May “Florrie” Glover.

Early Life

Horace Sr. came to Alberta, Canada, in November, 1919, to farm with his brother, Walter Henry Horne and his wife, Ada. After settling in, he sent for Florrie and Horace Jr., who was only 4 years old. They arrived in early Spring, 1920, leaving behind 8 year old Trevor, (Horace’s older brother) who remained in England with Horace Sr.’s mother.

While studying at Eastwood High School, Horace Jr. met Catherine Morgan and joined a choir just so he could see her more often. However, his plan backfired when he was thrown out after a week because he spent most of his time horsing around and bugging her! They started dating in Grade 12. Horace, a man of few words, was the Grade 12 Class President and delivered a speech that, “brought down the house”. Horace and Cathie went to Graduation together in 1933.

After High school Horace worked for his Dad loading and hauling cattle to the stockyards. Cathie enrolled at McTavish Business College after her father forbade her from going into nursing.

A few months after High School, the romance ended after an incident over a “silly hat.” Apparently, Horace took Cathie’s hat and when she demanded it back, he just threw it in the hallway and “took off!” Cathie’s Dad just said, “I always knew he was crazy!”

1933 was well into the Great Depression and jobs were scarce. After “unending interviews, humiliations and applications” Cathie started working for a nice Chinese couple at their vegetable store. They always gave her extra food to take home and made hot lunches for her. After a winter there, she worked at The Hudson’s Bay which led to full-time work.

Joining the R.A.F.

After saving enough money, in April of 1936, Horace Jr. began flying lessons at the Edmonton and Northern Alberta Aero Club at Blatchford Field, and qualified for his private pilot’s license on 1st August, 1936.

He was able to save for passage on a cattle boat across the Atlantic and arrived in London to pursue his dream. Success! He got a commission in the RAF on October 9th, 1936, and began Civil Training School for the RAF four days later, gaining his license on 5th December.

In January, 1937, Horace was posted to No.8 Flying Training School, Montrose, Scotland. He was now Acting Pilot Officer H. E. Horne, 703327, but he hated his given name and, like most RAF lads, acquired a nickname – “Jag” or “Jack.” Although the origins of this moniker remain obscure, it stayed with Horace for the rest of his life. Having completed his training, he was posted to 151 Squadron at North Weald (7/8/1937-13/9/1937) and then 56 (Fighter) Squadron, also based at North Weald, for roughly three weeks. On 11th October, Horace was transferred to the Reserve, and according to his passport stamp, he arrived back in Montreal on November 14th, 1937.

Back to Canada

Cathie only found out that Horace was in England from a newspaper column. It was January 1938, when she was returning from her lunch break at ‘The Bay,’ covered in snow, that she ran “headlong” into Horace and their lifelong journey began.

With the Depression, Horace was having a hard time finding a job and was “bugged silly about it at home.” He finally found employment at the Oliver Mental Institute as an orderly, which was degrading work, making $45 a month.

However, despite this Horace and Cathie got engaged. The ring cost $40 and took “weeks and weeks” to pay off. It was an unpopular engagement with both sets of parents and they were rarely ever invited to Florrie and Horace Sr.’s home.

The Outbreak of War

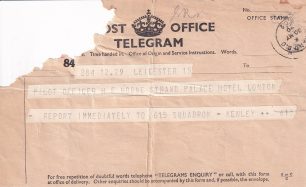

Horace longed to be back in the RAF and finally saved enough to travel back to England. In August, 1939, after a “sad, long goodbye” he was on a bus to Montreal and a boat over to Liverpool – the final destination being his Grandma Glover’s house in Leicester. The Air Ministry had no idea that Horace was already en route to England and sent a cablegram to his parents’ home in Edmonton on August 25th, ordering him to report immediately in London.

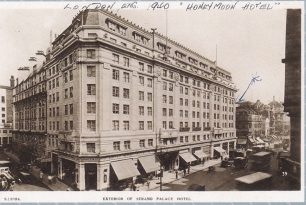

Despite going over to “get another stint in the RAF,” he neglected to pack his uniform! Florrie sent it to London care of the Strand Palace Hotel, where Horace was staying while he awaited orders from the RAF.

By 1939, Cathie had left ‘The Bay’ and started at Prudential Insurance Company. Florrie and Horace Sr. came to her office shortly after Horace’s posting telling her to “never expect to see their son again, as there was a war on.” Her boss told her they were “thoughtless and spiteful,” a sentiment Cathie remembered for the rest of her life.

In October, 1939, Horace sent a cable to Cathie asking her to come to England and get married as he was expecting to be posted to France in December with No.615 (County of Surrey) Squadron. He planned to send her money for her passport and passage but her parents flatly refused to let her go, despite her being 24 years old! This sent Cathie into a depression for a few months – she barely ate until she finally got her parents’ reluctant permission. Unfortunately, by this time, Horace wasn’t expecting her to come at all, and had spent all his money on ‘leave’ in Cardiff, before going to France.

The Battle of France

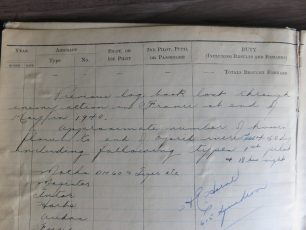

The 615 Squadron Operations Book records Horace’s arrival at Vitry, on January 1st, 1940:

“P/O R. E. Horne posted to this unit for flying duties, reported from Air Component.”

That same day 615 had received a visit from the Under Secretary for Air, Captain H. H. Balfour MC, MP, accompanied by the Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal W. S.Douglas MC, DFC. They brought the welcome news that the squadron’s out-dated bi-plane Gloster Gladiators were likely to be replaced by Hawker Hurricanes in a fortnight’s time. The squadron had moved to Vitry a couple of weeks earlier, because of the poor conditions at Merville, their previous base. The airfield at Vitry was a “vast improvement” and the accommodation seems to have been better too – Airmen’s billets were “more comfortable” and the Officers had their mess in the Cafe De La Grande Bretagne. During Horace’s first week the rear party of the squadron – ground crews etc – arrived and got settled in, along with the Motorised Transport section. The Right Honourable Winston Churchill MP visited Vitry briefly on January 8th, but most of the Officers and thirteen of 615’s aircraft were on duty at Abbeville and St. Inglevert. Horace isn’t listed among the officers who represented the squadron for his visit.

On the 11th, Pilot Officers Young, Fredman and Horne flew to Poix for an affiliation exercise with Blenheims. The frozen ground was making flying difficult and several of 615’s Gloster Gladiators were rendered unserviceable with broken tail units. All non-operational flying was stopped and Horne returned to Vitry with the rest of the Poix detachment on 13th.

The following day, fears of a German invasion through Belgium caused all leave to be cancelled. The severe weather was hampering operational flying and ground crews remained on the airfield overnight starting up the aircraft engines every two hours, in an effort to stop the engine oil from freezing. On January 29th, the squadron’s first four airmen left for Seclin to be instructed on Hurricane aircraft, with further groups following every few days. Converting to the modern Hawker Hurricane put the squadron on much more even terms with their adversaries, but was a tremendous challenge for 615’s relatively inexperienced auxiliary airmen, the exception being James Sanders who had first flown the Hurricane in 1938 with 111 Squadron, and had already logged over 1000 hours on the type.

At the beginning of February the weather was still poor but a thaw had set in. On 12th, a detachment of nine officers including the squadron’s new boys, Horne, Hugo and Mudie (who had joined the squadron on December 17th and January 26th, respectively) left for St. Inglevert for escort duties. All arrived safely. Horace must have welcomed the comparative luxury of their billets, in two hotels at Wissant.

At 3.10pm, Horace took off on his first (known) operational flight, a 40 minute patrol flying Gladiator N5577, along with F/O Giddings, F/O Murton-Neale and P/O Hugo. However the following day, all aircraft at St. Inglevert were reported as unserviceable because of broken tail wheels and reduction gears (caused by repeatedly running the aircraft engines on the ground when they were at an angle). By the 14th, the hard-pressed ground crews had managed to make three aircraft airworthy, but the weather continued to cause havoc.

On 28th February, the weather had cleared enough for two patrols to be carried out. Horace, (flying Gladiator N5577), accompanied F/Lt. Thornley on the second one from 16.50pm-18.10pm, escorting the leave boat.

The improvement in the weather allowed daily patrols to commence in March, and life got much busier for P/O Horne.

- 1st March, 0810-0940hrs – Patrol Line ‘B’, flying Gladiator N5577, with F/Lt. Thornley.

- 2nd March, 1455 – 1555 hrs – Patrol Line ‘B’, flying Gladiator N5577, with F/O Lionel Manley Gaunce.

- 3rd March, 1505-1610hrs – Patrol Line ‘B’ flying Gladiator N5577, with F/O Collard.

- 4th March, 1615-1715hrs – Patrol Line ‘B’, flying Gladiator N5577, with either F/O Collard or P/O Gayner.

- 5th March, 1000-1145hrs – Patrol Line ‘A’, flying Gladiator (serial unreadable), with F/O Collard.

- 6th March, 1000-1130hrs – Patrol Line ‘A’ flying Gladiator (serial unreadable) with F/O Fowler.

- 7th March, 0800-0900hrs – Patrol Line ‘A’ flying Gladiator N2304, with P/O Lofts.

- 9th March, 1050-1150hrs – Patrol Line ‘A’, flying Gladiator (serial unreadable) with P/O Gayner.

- 9th March, 1450-1610hrs – Patrol Line ‘B’, flying Gladiator (serial unreadable) with P/O Gayner.

Horace took no further part in 615’s operations in March – he was heading back to England for a very special event.

Wedding Bells!

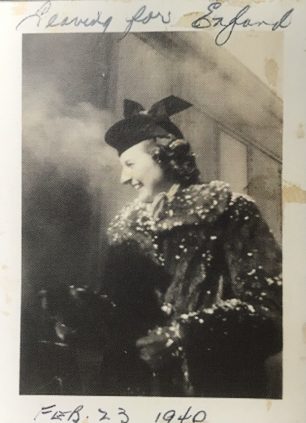

Horace had finally sent a cable and money to Cathie and she was booked March 1st, 1940, to reunite with him in England. Her eventful journey began on February 23rd and took her through the U-boat infested waters of the North Atlantic aboard the “Duchess of Richmond,” as part of a convoy escorted by Navy Corvettes. She carried a four-tier wedding cake, baked by her Uncle, as part of her luggage, which was checked at customs for sugar content!

Cathie and her cake arrived safely at Grandma Glover’s and on March 10th she returned home from the pub with Horace’s Aunt, to find Horace waiting for her. (A family member had managed to get a message to him in France). “As long as I live, I’ll never forget that second! He came over and wrapped his arms around me and it was sheer heaven! I was ready to die – happy!”

Cathie and Horace were married on March 12th, 1940, in a civil ceremony. They had a “wedding breakfast” reception at Grandma Glover’s and then took the afternoon train to London to honeymoon at the Strand Palace Hotel. Cathie wore a new navy suit from the ‘Army and Navy’ in Edmonton, which cost “a week’s wages.” Sadly, no picture was ever taken of their well-travelled wedding cake. Their nuptials were published in the society pages in Edmonton as there weren’t many pilots from the area flying with the RAF.

Ten glorious days in London with eight course meals, music, dancing and sightseeing passed all too quickly for the newlyweds. Horace returned to France with Cathie on the platform, “crying and waving goodbye.”

Cathie returned to Leicester, where she “existed”, occupying her time by volunteering at the canteen for the war effort. There was no indoor plumbing at the Glover’s so she walked five blocks everyday to bathe, which was considered odd as most people only bathed once a week.

Return to Combat

The situation in France was rapidly deteriorating when Horace returned. All of his belongings were eventually “bombed to hell” on the docks of Dunkirk and his flying logbook was also lost. This, together with the scant official records for this period, makes it difficult to track Horace’s movements during April and May – two months that had a profound effect on him. However, we do know that he was with ‘A’ flight and that by his own account, he returned from battle with bullet holes in his aircraft on several occasions. Once a German cannon shell went up through the floor, between his legs and out the top of the perspex canopy! He also crash-landed in allied territory in France after half of his rudder was shot off.

‘A’ Flight began the month of April at Vitry, before moving to Poix on the 12th, when their first Hurricanes arrived. Another move, this time to Abbeville, followed on 27th April – training on the Hurricane began in earnest and continued through the first week in May.

On May 9th, ‘A’ Flight moved to Le Touquet, intending to commence patrols over the Channel in their new Hurricanes, while ‘B’ Flight moved in to Abbeville to re-equip. Their plans were upset when Le Touquet was bombed by Heinkel He111’s, the morning after they arrived. Three of their new fighters were damaged (although two were repaired), and ‘A’ Flight returned to Abbeville in the afternoon.

On May 12th, ‘A’ Flight went to Vitry to carry out a patrol with 607 Squadron, and P/O Fredman was lost: “last seen chasing after a formation of enemy aircraft in the direction of Germany,” according to the Operations book.

The following day commenced at Vitry with escorting a Blenheim on a low-level reconnaissance of the Albert Canal. Timings went awry, when an approaching air raid meant that the Blenheim was ordered into the air 10 minutes early and only two Hurricanes made the rendezvous. F/Lt. Thornley managed to make it back to base after the sortie but his battle-damaged Hurricane was declared unserviceable. Everyone returned safely from a second Blenheim escort in the afternoon, but during the evening patrol F/O Murton-Neale was lost. A nerve-wracking day ended with a return to Abbeville, to commence patrols from there in the morning, before ‘B’ flight left for Vitry.

On May 15th, F/O Hedley Fowler failed to return from a bomber escort sortie in the morning. (He survived, was taken Prisoner of War and successfully escaped captivity). To counter the losses, seven new pilots reported for duty.

In the afternoon, ‘A’ Flight flew to Wavre and encountered a Henschel 126, 2/3 miles east of Gembloux, at 2500ft. Unusually, Horace’s combat report has survived:

300 yds 3 sec burst

Henschel staggered after first attack and pancaked in a field. Unable to press home attack due to heavy A.A. fire of all types. Attempted also to attack a balloon moored on ground but the latter was ringed with defence.

Result – machine hit 4 times.

Enemy casualties – Inconclusive 1

(The 615 squadron history compiled by Norman Franks credits a Henschel 126 on this date as a shared victory between F/Lt. Thornley and P/O Jackson).

Thornley’s luck ran out the next day when he lost his life during a patrol from Louvain to Wavre. Jackson was also shot down and taken Prisoner of War. Then, an evening patrol resulted in the death of F/O Young.

The situation was becoming more perilous by the day, but the squadron was ordered to move into Belgium to try and counter the German attack. F/Lt. Sanders flew to Evere, east of Brussels to see if it would be a suitable airfield, but found it full of Germans and took-off again rapidly!

S/Ldr. Kayll found Moorsele more accommodating, so 615 headed there, possibly with ‘A’ flight arriving first. The pilots got there ahead of the ground crews and had to start and re-fuel their own aircraft.

Patrols continued on 17th, with 615 reinforced by a flight of 6 aircraft and pilots from 245 Squadron, in order to get 12 aircraft in the air. A couple of the new arrivals got lost on their first patrol and damaged their aircraft in forced-landings.

An escort of 12 aircraft was ordered for 4.00am the following morning, but the Blenheim failed to arrive at Moorsele. Patrols continued with two more pilots getting lost and landing in Dunkirk.

On May 19th, the squadron ‘hack’, an un-armed Miles Master, was flown to Vitry to see if there were any serviceable Hurricanes left there, but found them all burnt out. It had just taken off when it was attacked by a Messerschmitt, and escaped narrowly with only one bullet hole through the perspex! Patrols continued from Moorsele with yet another loss – P/O Pexton, who had been shot down and suffered a leg wound. He made it back to England on 24th May, having already been posted “missing.”

German panzer units had passed Moorsele on both sides and the beleaguered squadron was in danger of being cut off. 13 Hurricanes and the Miles Master left Belgium at 4.30am on 20th May, heading for Norron Fontes – the ground crews had left the previous day only to find the roads jammed with refugees and service traffic. Inevitably, their trucks became separated. Reg Willis (615 ground crew) recalled that they had no time to sleep and no idea what would happen next.

On 20th May, patrols continued to be carried out with the last few members of the ground crew re-arming and re-fuelling the Hurricanes and destroying any equipment that might be of use to the advancing Germans. Eventually a transport aircraft arrived to take them back to England, escorted by nine of the squadron’s Hurricanes. The majority of the ground crew made their way back to England by sea, were accommodated overnight at Tidworth and then travelled by train to Kenley, arriving on 22nd May, only to find that no accommodation had been arranged. An empty girls’ school in Croydon had to suffice and the men were given blankets and had to make the best of it. The evacuation was so chaotic that stragglers continued to arrive back for days.

Horace later described his own escape from France to a Canadian newspaper:

Our squadron was pretty badly smashed up and we lost a number of our pilots. There were only three machines left in our squadron. One of them belonged to Gaunce.

According to Horace, 16 of the squadron’s pilots were stranded in France. They decided to ‘commandeer’ a French airliner based at the same aerodrome and held up the pilot at gunpoint, suggesting it would be in his best interests to fly them to England. The newspaper report continues:

The huge ship took off, but being unarmed it would have been ‘easy pickings’ for enemy fighter planes. The ship flew close to the ground, ‘hedge-hopping’ over hills and tree tops. It was smoky up above. In the haze and smoke, the pilots saw three machines high in the air. They looked like Me109s circling for the kill. Then the three machines dived. But there was no sound of machine-guns blazing. Instead, the machines fell into formation with the airliner. It was ‘Elmer’ Gaunce, waving his hands and with a huge grin on his face. He was signalling “Nertz to you.” “I was never so glad to see Gaunce in my life,” the Edmonton pilot remarked.

The only hint of this episode in the 615 diary is a remark for May 20th that:

three Hurricanes were flown independently to England, being unserviceable for fighting.

Horace called Cathie’s neighbour (who had a phone) from the south coast of England where he’d landed after the “Dunkirk business.” When Cathie met him at the Strand Palace Hotel he was a nervous wreck, mouth broken out in sores, thin, and infested with lice.

On May 30th, he received a telegram ordering him to report to 615 Squadron at Kenley, but he was one of a handful of 615 Squadron’s pilots that transferred to 242 Squadron at Biggin Hill shortly afterwards: Horne on June 2nd and then Pilot Officers Bush and Crowley-Milling on the 6th June. 242 was a unit mostly made up of Canadian pilots, but they were understrength and still embroiled in France. Horace doesn’t appear in the 242 squadron records. Instead, it seems that he resumed flying duties with 32 Squadron, who were also based at Biggin Hill, on June 12th, although he didn’t fly operationally and doesn’t appear in their squadron records either.

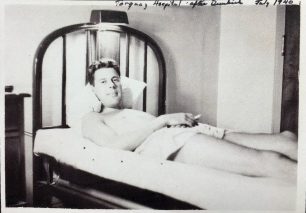

Finally on June 19th, Horace and most of the other members of his squadron that had served in the Battle of France, were sent on medical leave, “more exhausted than anything else,” according to Horace, but most likely suffering PTSD by today’s standards. He was admitted to a hospital in Torquay on June 28th, for convalescence, where he remained, with Cathie at his side, (staying in a local bed and breakfast), until September 25th.

On 29th September, Horace went before a Medical Board and was classified ‘A2hBh’ (Fit for limited flying duties, fit for ground duties, home service only). He resumed flying duties on October 6th, 1940, at 57 Operational Training Unit. Log book entries show him flying with No.22 Elementary Flying Training School (Refresher Course Pool) from December 2nd, 1940. At the end of February 1941, Horace went before the Medical Board and was graded ‘A1B,’ (fully fit). He continued to instruct until May, 1941.

An Extraordinary Letter

Nine days before his next posting to No.22 EFTS, Cambridge, Horace reflected on his experiences during the Battle of France in this letter to his Father:

“Received your letter of Oct. 22 with the snaps enclosed. We both seem in the same boat with this letter writing business, and I’m positive that the said boat doesn’t always dock with our mail on board. However, that is to be expected in these days.

I am still one of the forgotten “men” around here, as no word has yet come through about my posting. I didn’t mind the waiting at first but it’s now beginning to gall me somewhat. One can have too much of a good thing, especially inactivity.

With regards to this D.F.C. and medal question that you bring up. Most of them are undoubtedly well deserved. But there are also cases in which a pilot receives a D.F.C. through pure luck or “wangle”. For instance, when I got back from France I left — immediately. I heard that the squadron C.O. was asked to recommend for decorations. The C.O. got the D.S.O. and D.F.C., X got a a D.F.C. for “taking part in many dangerous jobs to stem the German advance etc.etc.” It so happens that we flew together on all of these jobs and I shot down more Huns than he did; also I was the first pilot in the squadron to get a Hun; in fact I’d bagged 2 before anyone else made a score. I guess I’m bragging a bit here, and I don’t want it to go any further, but it serves to show you that my “luck” wasn’t “in” due to leaving —.

One squadron over there was given a number of D.F.C.’s to be awarded to the pilots. The C.O. was very impartial and as he didn’t want or know who to favour , he had the old “pull out of the hat” game. So you see.

Believe me, I say good luck to all the fellows who receive decorations. God knows, the R.A.F. deserve all they can get, because as Churchill says, “Never in the history of human conflict, etc.etc” and I take my hat off to those chaps with the blue and purple ribbon.

So far I haven’t done a hell of a lot in this war, but I don’t remember missing many patrols in France. The air component in which our squadron was one of about four, lost 7 out of 10 pilots, so you can see that those boys fought to nearly the last man and machine, a campaign which will probably not receive the recognition due, because of the fact it is so overshadowed by other events.

The 330 odd thousand that got away from Dunkirk can thank the fighter pilots for keeping the Jerry dive bombers away from them. As it was, it was hopeless to stem all the tide. The boys that fight over here can at least be sure that they won’t get A.A. [anti-aircraft] fire, and if they bale out they won’t be taken prisoner. We sometimes had the job of ground straffing troops, which in my estimation is the most dangerous job of the war, intense A.A., and if you have to bale out they shoot you on sight, not that I blame them at all.

I’ve been hit about 5 times by A.A. fire, so I can assure you that the Hun A.A. is damned good when they can hit a Hurricane at 18,000ft, such as they did mine. I really don’t know why I’m talking like this, because I’ve made it a rule not to shoot a line, so I hope you’ll pardon the diversion and keep it under your hat. I’m no blinkin’ ‘ero and I don’t suppose I ever will be but up to the present I’ve got no medal and both feet on the ground, & I prefer the latter for the while. How many D.F.C. pilots I know who never even lived long enough for the investiture. After all, a man’s reward in this war is knowing that he’s doing his bit to help King and country, and personally I’m no medal or fame hunter, and I never have been. I don’t mean that I’m yellow, because the only thing I’m afraid of is being afraid. I can’t begin to tell you the feeling of exhilaration one gets when under fire or in action to realise that you can take it. A man with no fear in his makeup isn’t brave. The one who forces himself to face death in spite of the fact that he would rather run away is just as much of a hero as the cold nerved pilot who doesn’t know what fear is.

There were times in France when, before a patrol, my stomach would writhe at the thought of meeting a violent end, but I put on an act of don’t-give-a-damn rather than let anyone know it. We all had a talk one day and the confessions came out that we didn’t exactly look forward to getting shot down and were glad to get the job over with. But with the exception of one ot two, we did our job to the best of our ability and the Hun paid dearly for his victory at that time.

You’re right when you said that I was always lucky. But I never flew without I looked like a curio shop – silk stockings, lockets, locks of hair and god knows what else. I laugh now when I think of it. In Boulogne just before the Blitz started I bought a gold locket in the shape of a heart and I hung it around my neck with a fine chain. On it was engraved —-, and inside was a small lock of the loveliest hair in the world.

I’d have cut off my arm before flying without that. Thus I am still kicking and one day soon I hope to make a few more Huns pay for the murderous attack on this country. In fact now that I think about it I acted a bit medieval although no one knew it but myself.”

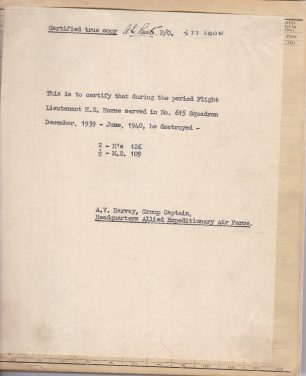

Horace’s supposition that his departure from 615 Squadron had led to his achievements in combat being overlooked appears to be correct. Many records from the Battle of France were lost during the squadron’s hasty evacuation and Horne’s claims don’t appear on the list of 615’s known victories, though it is noted that the squadron was believed to have brought down 32 enemy aircraft.

Teaching the Next Generation

On September 19th, 1941, Horace was promoted to Flight Lieutenant. Now instructing pilots at No.21 Elementary Flying Training School at Marlow, they had the good fortune to be billeted at a beautiful house on the Thames, in Cookham. The estate was owned by Sir Algernon and Lady Lee Guinness. He was the 3rd Baronet of the famous Guinness Brewery Co. Cathie remembered them as “very lovely” people. The last entry for Marlow in Horace’s logbook was dated November 27th, 1941.

At the end of 1941, Horace was posted back to Canada as a flying instructor. His first stop was at No.2 P.D.C. (Personnel Dispatch Centre) in Wilmslow, near Liverpool, prior to departing on December 21st.

He arrived back in Canada on January 3rd, 1942, a combat veteran of 26 years old.

While Horace was en route to Canada, Cathie was embroiled in bureaucracy between the Air Ministry and the High Commissioner for Canada as she tried to arrange her own passage home. Approval to sail came on December 18th, 1941, along with her new passport (in her married name) and an exit permit. An urgent telegram arrived on January 2nd, detailing the departure arrangements. She barely made it to Lloyd’s Bank in London to pay the £38 fare for her passage.

No rail or ship schedules were known in case they fell into enemy hands, so Cathie made her way, by rail, to Glasgow after midnight on January 6th to await instructions. Finding no accommodation, she slept on the station floor with another young war bride and was awakened at 6am by a railway official who directed them to a strange “dive-of-a-place in an attic” where they were given a slice of bread and a cup of black tea before being herded down to the harbour and ferried out to their ship, “The Montcalm”. Her 8x10ft cabin held four bunks and a wash basin that produced about a gallon of fresh water every two hours. Down the hallway was a salt water bath. She arrived safely in Halifax, Canada, two weeks later and begun the cross-country train trip to Calgary, where she caught a flight to Edmonton and was finally re-united with Horace on Sunday, January 25th, 1942. A few days later, Horace’s unit moved to Assiniboia, and he resumed his duties as a flying instructor.

In May, 1943, Horace was posted to the Central Flying School at Trenton, Ontario, but less than a year was to pass before duty called him back across the Atlantic again, leaving Cathie in Edmonton, pregnant with their first child.

Horace was posted from Headquarters A.D.G.B. (Air Defence of Great Britain) to No.577 Anti-Aircraft Co-Operation Squadron on 19th May, 1944, attached to Sealand. The following day he flew on a weather test as a passenger with F/O Clark – the conditions being so poor that Co-Operation flying was cancelled for the morning. On 30th May, Horace returned to Castle Bromwich, still flying with No.577 Squadron and was posted to No.57 O.T.U. for operational training on 6th June, 1944 (D-Day) according to 577’s records, though he may, in fact, have been instructing.

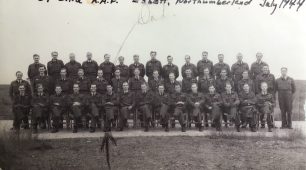

No.57 O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit) was based at Eshott, Northumberland. O.T.U.’s were the last stage of training for pilots before they joined operational units. Here they would become familiar with the aircraft they would fly in combat and learn air gunnery and dog-fighting techniques. It was essential that their instructors at this stage were combat veterans who could pass on the techniques that had kept them alive in battle.

Horace’s application to resign his commission in the RAF on appointment to a commission in the RCAF was approved on January 3rd, 1945, and his last RAF flight, before being repatriated to Canada, was on March 9th, 1945, with No.288 (Anti-Aircraft Co-operation) Squadron at Church Fenton. He was posted to the RCAF ‘R’ depot at Warrington on 23rd March.

Peacetime

Horace returned to a posting at Trenton, Ontario, making his first flight on June 19th, 1945, followed by No.2 Flying Training School, Yorkton, in October, and then No.2 Communication Flight in Winnipeg, where the Commanding Officer reported that Horace had, “proven himself to be an able and experienced pilot.” He made his last flight on March 29th, 1946, and was released on September 22nd, 1948, having instructed on Harvards, Cornells, Ansons, Masters and Beechcraft Expeditor aircraft as well as Hurricanes and Spitfires (“the most beautiful aeroplane ever made”).

Horace and Cathie had four children, Brian, Terry, Margaret and Lorraine.

After leaving the RCAF, Horace worked as an administrator for Canada Pension Plan until his retirement in 1980. He passed away in August 1983 as a result of complications from a medical procedure. Cathie passed away suddenly in 1991, after a stroke. Her ashes were laid to rest beside Horace in Ottawa.

Comments about this page

great research. Horace Arthur Eldrid Horne was my great Uncle. his brother, Kenneth Horne, was my grandfather. I’m trying to build our family tree (on Geni.com) out for my kids to see and this was really interesting. I was in France this summer and didn’t know I was roaming around the same ground that Horace was during the War.

It is nice to see that at least a few of these heroes of WW II are not totally forgotten since the freedom of my generation was bought and paid for by their sacrifices.

Thank you for posting this amazing story about my Grandpa.

Add a comment about this page