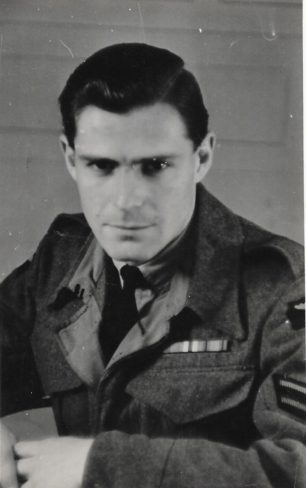

Aircraftman 2nd Class Ernest Bailey's Memories of Kenley in 1940

Ernest Leonard Bailey was born on 19th March, 1920, in Birdham, Chichester, where he worked as a painter and decorator. Realising he would soon be called up, Ernie volunteered to join the RAF, thinking that would be better than the infantry. He enlisted at Uxbridge on his 20th birthday, in 1940, and was sent to Morecombe to do his Initial training.

Exactly one month after joining up, Ernie took the train from Morecombe to Whyteleafe station and walked up the hill to his first posting at RAF Kenley. He was soon settled in his billet – No.D.2 barrack block, near to the airfield’s main entrance, and was assigned to the Lookout section, manning the post on the roof of the Watch Office, which was attached to the side of one of the hangars and faced out over the airfield.

Two airmen would man the post on an eight hour shift pattern, night and day. Their job was to report all aircraft movements, take-offs and landings, to Control by telephone, although they never received any acknowledgement that the information had been received. They had no special equipment, not even a pair of binoculars, and had received absolutely no training in aircraft recognition. Ernie could recognise Spitfires, Hurricanes and Fairey Battles, but had no idea about enemy aircraft and would have struggled to differentiate between a Messerschmitt Bf109 and an Allied fighter! He remembers that Spitfires tried to avoid landing on the short runway, if possible, because their speed made the landing tricky.

Ernie settled into the routine of his new life and remembers the period of the Battle of France as “business as usual.”

There were plenty of air raid warnings but Ernie doesn’t remember any actual bombing, so the raid on 18th August, 1940 – ‘The Hardest Day’ – came as a terrific shock.

It was Sunday; Ernie had eaten his lunch and was back in his barracks, when the warning sounded on the Tannoy. As he was off duty, his orders were to take a rifle from the rack and man one of the slit trenches, which he dutifully did despite having no ammunition or even a bayonet. One of the other men knew where to go and Ernie found himself waiting near a trench between one of the hangars and the Medical block. He watched the occupants of the Sick bay come out and head for the crescent-shaped shelter nearby.

As the Attack Alarm sounded, he got into his trench with three other men. They were calm but frightened. He doesn’t even think they had tin hats on.

One Dornier Do17 flew right over them at rooftop height. It was so low that Ernie could clearly see the pilot and navigator. The hangar nearby was hit and Ernie remembers the intense heat as it burnt, but still stayed put in his trench until ordered to quit the area and return to the main entrance. There weren’t enough spades and shovels, so they couldn’t do anything to help the stricken occupants of No.13 air raid shelter, next to the Sick Bay, which had been hit at either end, trapping the shelterers, and killing Dr. Cromie, No.615 Squadron’s Medical Officer.

Despite the damage and loss of life, the airfield was serviceable the following day. The barrack blocks were undamaged and Ernie stayed there for a couple of days before being moved to a requisitioned house in Anne’s Walk, (either No.3 or 4).

Ernie remembers the rest of his time at Kenley as largely uneventful.

His social life was hampered by a lack of money – as an AC2, he was only paid 2 shillings a day, which he received every fortnight. However, Ernie was a keen cyclist, so at the first opportunity, he collected his bike from Birdham, and from then on would cycle back to Birdham from Kenley when he had the chance, returning the following day. He also enjoyed the occasional stroll in Caterham park.

In October 1940, Ernie was posted to No.4 School of Technical Training at Melksham, Wiltshire, to train as an Instrument Mechanic, Group 2. From there he was sent to the Pilotless Aircraft Unit at No.32 Maintenance Unit, St. Athan, where he stayed for 1 1/2 years working the DH82 “Queen Bee” – pilotless derivative of the Tiger Moth, developed for use as a gunnery training target.

From there, Ernie went for further training and took his Group 1 Instrument Mechanic ‘s course, which he passed in 1942. In 1943, he was posted overseas to Sicily and then Italy, for 18 months, before being de-mobbed on his 26th birthday, in 1946.

Post-war, Ernie returned to Birdham where he worked as a self-employed painter and decorator for 60 years. In April 2023, he passed away peacefully at home, aged 103.

Rest in peace Ernie and thank you for your service.

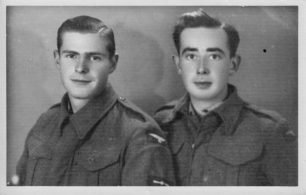

We’re very grateful to Ernie’s family for the photo and permission to share his memories.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page