I, John Brian Crawford, was born 12th April 1934, the first child of my parents, Albert John Botcherby Crawford and Lily Dorothy May Baron, who had married in 1930 at St. Mary’s Church, Summerstown, London, SW17. Both my parents came from large families – my Dad was one of thirteen and my Mum was one of five.

John Crawford and family at the RAF Kenkey Tribute, 2nd April 2023, (Photo: Neil Broughton)

In 1940, we were living in Earlsfield when the threat from Germany meant that children from the cities were evacuated to safer rural areas of the country. My younger sister Daphne (aged 4) and I (aged 5) were put on a train at Paddington with lots of other children and made the long journey to a villlage called Gilwern, in Wales, near Abergavenny. We went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Williams, a strict couple with no children of their own who frequently spoke Welsh, which we picked up. After a few months our Mum came to visit us and took us back to London, but it wasn’t long before we were bombed out of our house and had to move. Mum then took us back to Wales, but this time rented a house for us and our new baby brother, Malcolm, who was born in July, 1940. This lasted about six months before we returned to Dad in London and then went to stay with distant relations in Barrow-in-Furness. The beaches were great but had been mined and roped off. One of our school pals was blown up when he entered an area that had been mined and after that Mum decided to go back to London, where Dad had just rented a three storey townhouse in Merton Park, where they lived for the rest of their lives.

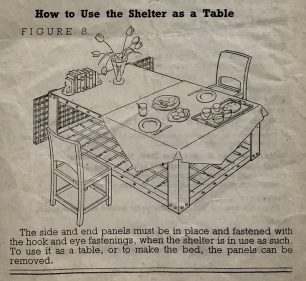

No sooner had we returned to London, when a new menace began to threaten our safety – V1 and V2 vengeance weapons. We had to shelter almost every night in the Anderson air raid shelter which belonged to relations living next door, but this was quite a squeeze so Dad installed a Morrison shelter in our kitchen, which served as a table most of the time. My Dad was an ARP warden after his day’s work, often out saving people, so when he did sleep it was when there were no air raids. We had a doodlebug land and explode just across the road in the corner of the playing field and, though it was a good distance away, its blast blew out the front windows of all the houses on Manor Road.

The Ministry of Home Security’s leaflet, “How to Put Up Your Morrison Shelter,” actually suggests using it as a table during the day.

(From the collection of Robin Grainger)

At St. Mary’s Junior School, I remember that, on hearing the air raid sirens wailing, we would take our places in the brick built shelters in the playground, sitting on wooden benches, and sing songs to keep us from being frightened.

When I was 11 years old, I moved to the senior school about 100 yards away from the junior school and at 13, I passed an exam to enter Wimbledon College, where I studied engineering for almost three years and thoroughly enjoyed it. However, all good things come to an end and, at 16, it was time to leave and find work.

The college arranged interviews for us leavers and my first interview was with Otis Lifts, a large company in London, but I wasn’t very impressed with them or they with me, so no job there! I had more luck with my second interview, at G. C. Pillinger in Sutton, who specialised in oil burners and water systems – they offered me a five year engineering apprenticeship.

While working as an apprentice at Pillingers, I was entitled to attend college, in fact, my old school, which was now a Technical College. This was to study for my Ordinary National Certificate, needed for a professional engineer. I had not finished my studies when I was called up for National Service, so finished all my studies after I was married, at night school.

The Royal Air Force

When you were called up for National Service, you had to attend medicals, and if fit, more interviews to determine what service you were to join: Army, Navy or RAF. At my interview it was announced that the only option was Army.

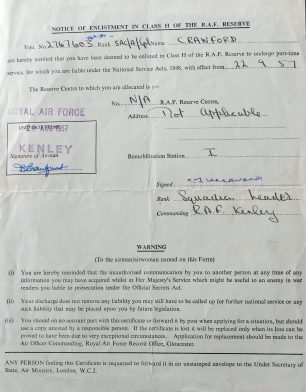

John Crawford’s Enlistment Notice (From the collection of John Crawford).

I boldly stated that my uncle, Frank Crawford, was a Group Captain in the RAF on Air Traffic Control and that he particularly wanted me to follow him. Strangely, no one checked my request, and so, in 1955 I joined the RAF. My first camp was at RAF Cardington in Bedfordshire, where we were kitted out with our uniforms, boots, shirts, undies etc., and did a small amount of drill exercises to get us used to discipline. Quite a few of the new recruits had never been away from home before, and got very upset, but I guess as I had been evacuated and was older than most of them, it did not affect me.

I was then sent to RAF Bridgenorth in Shropshire, this was a discipline and drill camp, where we got fit and did as we were told. We were drilled every day marching or running with full packs on our backs and carrying rifles. It was very hard and not a pleasant experience, but it developed a strong sense of comradeship, and more importantly, a self-discipline. This course lasted for 8 weeks and I was allowed home one weekend(a 48 hour pass), for a break to see my family, but had to travel back over Sunday night so as to be in camp and ready for duty by 0800 hours.

Whilst here at Bridgenorth we had lots of inoculations for every disease known, it seemed. Well, I got vaccination fever and was confined to bed in my billet for four days. I could have gone to the infirmary, but then I would have been back flighted, and then have to start the course from the beginning again. The NCOs (Non-Commissioned Officers) were helpful, which was not like them at all! When I was better they gave me extra drill sessions which let me catch up with all my colleagues from the billet.

The course finished, and we went on to our designated trades at another station. My training station was RAF Shawbury, again in Shropshire, for 6 weeks to train as an Air Traffic Control Clerk. I really enjoyed the course, and managed to play a lot of football there, although there was still plenty of drills and marching, but nothing like the severe hard time at Bridgnorth. My pay was £2 per week, I sent home to Mum most of it for my keep.

RAF Kenley

After my training came the postings to where you would go, probably for the rest of your two year time. This was decided by tribunal, who asked where you would like to go and then they would send you to an opposite! I told them that as I was a single guy, I would like to go abroad and see the world so I said; “How about the Far East?” Then, as a joke, “How about Surrey?” To my amazement, I was given a posting to RAF Kenley in Surrey. Prior to my final posting, I was sent to Moreton-in-Marsh, to be instructed in fire-fighting procedures. Part of my air traffic duties would be to organise a fire crew, that were always to be in attendance when the airfield was open. I also learnt to drive a fire engine – these had six forward and six reverse gears. Great fun!

Kenley’s Watch Office on the side of the last remaining Belfast Truss hangar. (Photo: Allan Melmore)

So I went to RAF Kenley, part of Home Command, and after the initial disappointment, I settled in there, and had a most wonderful time. The senior officer was terrific, not a disciplinarian, left us to self discipline, which was a credit to him, and I believe helped us to become better people. I arrived at RAF Kenley just after they had finished filming the Battle of Britain epic, “Reach for the Sky” with Kenneth Moore portraying Douglas Bader, who lost both legs in a crash. He kept on flying and ended in a prisoner of war camp. At its premiere in London, we all wore our dress uniforms for the opening ceremony, and then enjoyed the film. I sat next to a famous actor who had played a German Commandant in the film. He was Eric Pohlman, a very pleasant gentleman.

Inside Kenley’s Control Tower, also known as the Watch Office. (Photo: John Crawford).

As an Air Traffic Control clerk, I worked in the Airfield control tower overlooking the whole airfield, and directed all planes in and out, the traffic was usually fairly light, but we had to plan all the flights during the week and organise night flights and weekend for cadets and other flights including the Army and Gliders.

Playing records in Kenley’s Control Tower (Photo: John Crawford)

The Army had Tiger Moth aircraft and often flew in from Hendon for lunch in our Officers’ Mess. They would fly in formation and if the weather was not perfect, would call for directions following main roads and us telling them to turn left at the next traffic lights, then follow that road up the hill and then you will see us, very primitive, but nice people just out for a jolly and some lunch. They quite often would leave some goodies for us all to share.

Inside Kenley’s Control Tower (Photo: John Crawford)

We also had the Air Training Cadets to organise and they went up in an Anson aircraft, we had to go with them. They generally enjoyed it, but it was a chore for us and the ground crew if they were taken ill and left us a deposit to clear up.

The Watch Office was demolished along with Kenley’s last Belfast Truss hangar in 1978. (Photo: John Crawford)

We had many of the Battle of Britain pilots stationed here, quite a few Polish. They were wonderful men and we thought it a privilege to accompany them when they did instrument flying, we had to be their eyes, so they could keep their pilot license. They were terrific pilots but when the instrument flying finished, they would go crazy and do aerobatics and “shooting clouds.” Needless to say, we were frequently scared and ill, so we and the ground crew had extra work to do cleaning up. The aircraft they used were Chipmunks, we also had Ansons and Jet Provosts, our runways were not long enough for the more modern jets.

On one occasion, when the airfield was closed due to fog and low cloud, we heard jet engines roar above us and then several planes flew down our runway at nil feet – they were out of Biggin Hill and were returning from an exercise due to the bad weather. They were well off course as Biggin Hill was 25 miles east of us. We warned them off by radio and all went away except one who came round again and attempted to land. This he did but because our runway was short he overshot the end and finished up in the mud in an adjoining field. We rushed out the fire tenders and then some of us. Fortunately he was fine and we took him to the Officers’ Mess, but as his plane was fully armed we had to mount 24 hour guards on it, till a crew came and disarmed it and took it away in bits by road. He, we understand, got into serious trouble for his action. Quite exciting for us, not for him! The reason for the 24 hour guard with weapons was that the IRA were a danger then. They did try to get into our guardroom whilst I was there but did not succeed.

On all RAF stations, there are canteens called NAAFIs, which prepared food all day and most nights at very reasonable prices. Well, our unit suddenly raised up its prices and the quality dropped, so we (I) decided to set up in competition for breakfasts.

Kenley’s Institute and Dining Room. (Photo: John Crawford)

We had several stores and outbuildings on the airfield, so I scrounged some electrical hot plates etc. and started to collect orders from the ground crews, firemen, guards and clerks and cooked breakfasts, rolls, sarnies, plenty of hot food. We would take a Jeep down to the village, get all the items fresh, bring back, cook and then deliver. Our prices were cheap and well below the NAAFI’s, so we did a roaring trade. Any profit went to our senior officer’s charity. It became very popular, we were having a job to cope, but then the NAAFI noticed its lost trade and we were shut down and reprimanded, as we had infringed the rules and without the interception of our officer, could have been in serious trouble. The NAAFI did, however, reduce its prices and the quality improved.

Another occasion there had been a spate of thefts around the town, nothing dreadful, just road signs, advertising boards and products and even some street name signs and they all ended up in our night flying store out in the airfield [ the shelter at the back of The Tribute blast pen- ed.] and some even in my room in the billet, I was now in charge of the complete billet and so had my own room. I was sitting in a cinema in Wimbledon during a day off, with a girlfriend, when onto the screen came a written message, “Would Corporal Crawford contact his RAF Senior Officer immediately.” Scared to death, I managed to get home and used Aunt Nell’s phone, to learn that the RAF Police had been informed that our stores had stolen goods in them, that I had the only key, and I would be back in camp the next day. I hurried back to camp and, with the help of my pals, took all the borrowed items from the stores and my room, and buried them all at the end of the runway – as far as I know, they are still there! A close call, for when the Police did arrive there was nothing to find, as I did have the key I could have been in real trouble.

After that I kept nothing dodgy in my room, although my room was rarely checked during the weekly inspections of the billet. Early on I would go home to Merton after my daily shift ended, as long as I was ready for the morning shift at 0800 hours. When we had night flying duties it got more complicated. If I went home I would cycle the 14 miles there and then do the 14 miles back, so I decided to stay on camp, after all I did have my own room. Now about this time skiffle was very popular, so several of us decided to form a group – we called ourselves the SKI-FIS.

The SKI FI’s in their blue boiler suits with orange socks and matching neckerchiefs. John is on the left with his snare drum. (Photo:John Crawford)

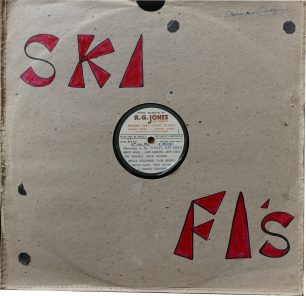

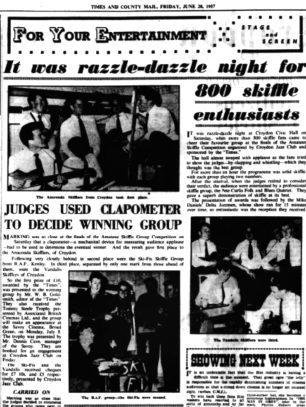

We had a good musician who played piano and guitar, another who played the guitar quite well, a bass player (tea chest, broom handle and string) a washboard scratcher and me on a snare drum. We used to practice in the evenings on a stage in the NAAFI hall, behind the curtains, and had a great time. We played all the old Lonnie Donegan songs, which were old American folk and blues numbers. One night we made a tape of the rehearsal, you can hear it as we had a record made later and a cassette of it. It shows the fun we had, although it is very dated now. We eventually played at local dances, social evenings, and then we entered a skiffle competition at the Davis Theatre in Croydon, and came second, and won a grand prize of £7.50 to be shared

The SKI FI’s record. (From the collection of John Crawford)

between the five of us – we were now professional musicians. Enjoying the skiffle as we did, we had a small following of nurses and other local girls. One girl, Anita Sinkinson, was a wonderful singer and I tried to get her to be part of our group but the others were not keen and it never happened. I still think it would have ben good for us and her. I believe that later she did become a jazz singer with a top band and changed her name.

The Times and County Mail report The Ski-Fi’s second placing in the Skiffle competition on 28/6/1957.

My fellow skiffle man, Brian Platt, eventually married Anita’s best friend and they moved up to Birkenhead, his home town, when he was discharged from National Service. He was a window dresser by trade and a terrific cartoonist. [John says that it was Brian who drew the Buggs Bunny cartoon in the Tribute pen shelter – he had painted the same cartoon on motorcycle helmets for his friends].

The Buggs Bunny cartoon which John recognised as being drawn by his friend Brian Platt, inside the air raid shelter at the back of the Tribute blast pen. (Photo: Linda Duffield

I had a girlfriend then called Mary Croydon who lived close by in Merton, I introduced another colleague, Ray, to her family and he married Mary’s sister Ann. I must be a matchmaker. I have lost touch with all of them now.

I did night flights duty as often as I could, I got quite a bit of time off, so I would go back to my old company to earn some extra money, quite regularly, it also enabled me to play more football on Saturday and Sunday.

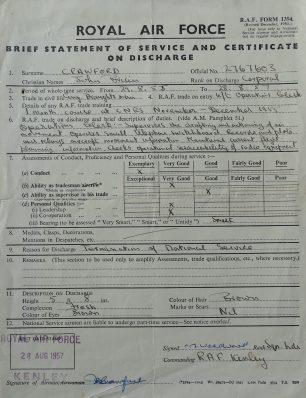

John Crawford’s Discharge Certificate

When the two years National Service was complete, I was still on reserve in case of war, but now I was demobbed and could resume my employment at Pillingers, who had now moved from the old house in Sutton to a new factory and offices in Purley Way, Croydon.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page